Wrath and Mercy, Law and Grace

By Debra Dean Murphy

June 8, 2010

Third Sunday After Pentecost – 13 June 2010

1 Kings 21:1-21a; Psalm 5:1-8; Galatians 2:15-21; Luke 7:36-8:3 (Revised Common Lectionary)

The readings for this Sunday, taken all together, create some unsettling tensions.

The passage from 1 Kings recounts the refusal of Naboth the Jezreelite to sell his vineyard to his neighbor, King Ahab. When the king goes home to sulk about this, his wife Jezebel takes charge and soon enough a property dispute has led to a crime scene: Naboth is wrongly defamed and summarily executed. Ahab gets his vineyard after all.

Psalm 5 reads something like Naboth’s own prayer from beyond the grave in which he petitions Yahweh to “give heed to my sighing . . . for you are not a God who delights in wickedness . . . you destroy those who speak lies” (vv. 1, 4, 6). Back in 1 Kings, the shocking story does indeed conclude with a chilling warning delivered to Ahab by the prophet Elijah: “I will bring disaster on you” (v. 21a).

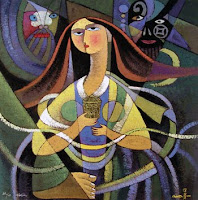

Over and against these Old Testament texts (to put the matter contentiously), are the readings from Galatians and Luke. In the gospel lesson, another woman takes center stage: the “sinner” who disrupts a dinner party at the home of Simon the Pharisee by weeping at Jesus’ feet, bathing his feet with her tears, drying them, kissing them, and anointing them with ointment. Through the centuries this unnamed woman has been interpreted as something of a Jezebel: a “loose” woman with a past and no sense of her proper place.

When the host objects to the woman’s behavior (he’s the only one to do so in Luke’s version of the story; the other three gospels describe the scene differently), Jesus defends her. He admires her hospitality and commends her “great love” (v. 47). And whatever sins she has committed he forgives forthwith, sending her out in peace.

A surface reading of the Galatians text can reinforce old, unchecked tendencies that pit the Old Testament’s alleged preoccupation with sin, judgment, and the wrath of God against the New’s purported emphasis on grace, love, and forgiveness. Some have imagined that Paul, in his testy epistle to the disciples at Galatia (and in other letters), renounces the whole of Israel’s scripture and tradition along with the particular practice of circumcising Gentile converts. But Paul is no supersessionist. For him, the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth constitute a continuation of Israel’s life with God. Paul’s theology is less doctrinal than narratival: he locates the Church within the story of Israel’s election, judgment, and redemption. The old divisions do not hold; law versus grace turns out to be a false fight.

On its own, the story of Ahab, Naboth, and Jezebel offers an instructive word about the abuses of institutional power and the legitimate grievances of those who are powerless—a word that couldn’t be more timely in this era of corporate greed and irresponsibility. But the lectionary asks us to read 1 Kings in concert with Luke 7. It juxtaposes the stories of two sinful women—one whose sins are left unnamed; the other’s all too vividly reported. It asks us to consider harsh judgment: both Elijah’s condemnation of “what is evil in the sight of the LORD” and Jesus’ stinging rebuke of Simon’s lack of generosity and hospitality. And it shows us, through Jesus’ words and actions and Paul’s reading of Scripture and the Cross, that Jesus sides with the sinner every time. Every sinner.

The readings for this Sunday, taken all together, create some unsettling tensions. But they are worth our time and attention and may tell us something about how wrath and mercy, law and grace, are—for those who claim the name “Christian”—always of a piece.